Notes from “Explosante fixe”, Exhibition Catalogue at Centre Pompidou

Some notes are in French, I do not fully translate everything, only the most important bits. I’ll translate later what will actually be used in the essay.

André Breton, L’entrée des mediums (1922)

Definition of Surrealism

“un certain automatisme psychique qui correspond assez bien à l’état de rêve, état qu’il est aujourd’hui fort difficile de délimiter.”

Breton “hasard objectif”

George Bataille “L’informe” “Bassesse”-> chûte

Salvador Dali

“Photographie, pure création de l’esprit” (1927)

in Dawn Ades, “Salvador Dali”, Thames and Hudson 1982

“Ils trouvent vulgaire et normal tout ce qu’ils ont l’habitude de voir tous les jours, si merveilleux et miraculeux que ce soit”

Dali, “Film Art, Fil Antiartistico”, Gazeta Literacia (1927), in Dawn Ades

“Le monde du cinema et de la peinture sont très différents: les possibilités de la photographie et du cinéma résident precisement dans cet imaginaire illimité qui nait des choses elles-mêmes. Un morceau de sucre sur l’écran peut devenir plus grand que la perspective infinie d’édifices gigantesques.”

Dali, “Psychologie non euclidienne d’une photographie”, Minotaure 7.

“La donnée photographique est toujours et essentiellement le plus sûr moyen d’expression poétique et le procédé le plus agile pour saisir les plus délicates osmoses qui existent entre la réalité et la surréalité. Le simple fait de la transposition photographique implique une invention totale: la capture d’une réalité secrète.”

Salvador Dali – Realité Secrète

The image reflects reality but forces people to see the world without prejudice/preconception. Therefore the representation of the world presented by the image (i.e. By Art) is truer than the world directly gazed at.

-> the reflection of the world in the mirror (=Art) is truer than the direct image.

-> Alice Through the looking glass

Benjamin Péret, Minotaure 12-13

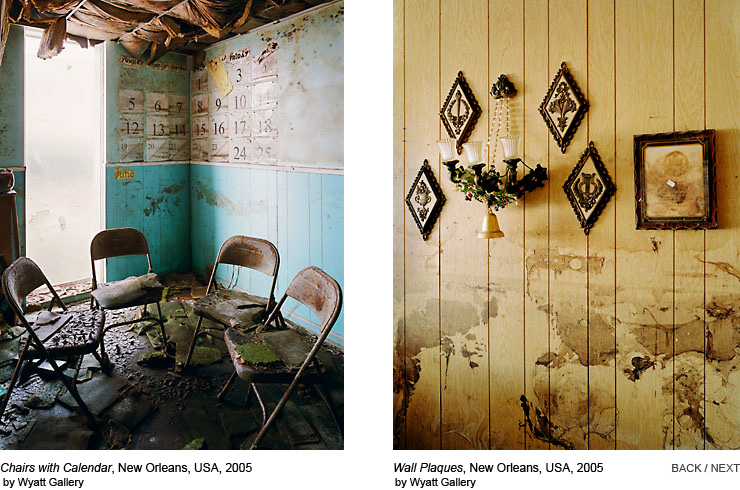

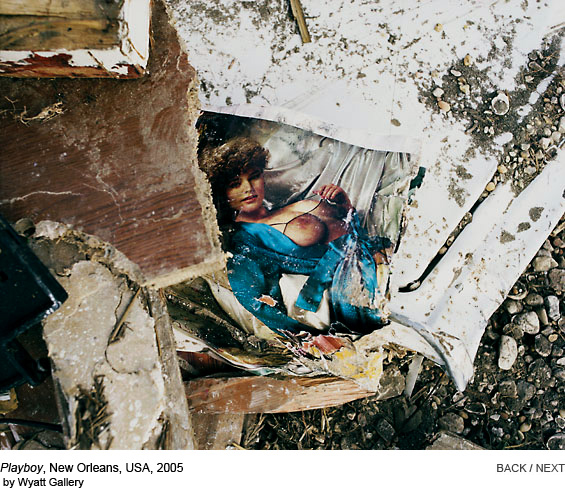

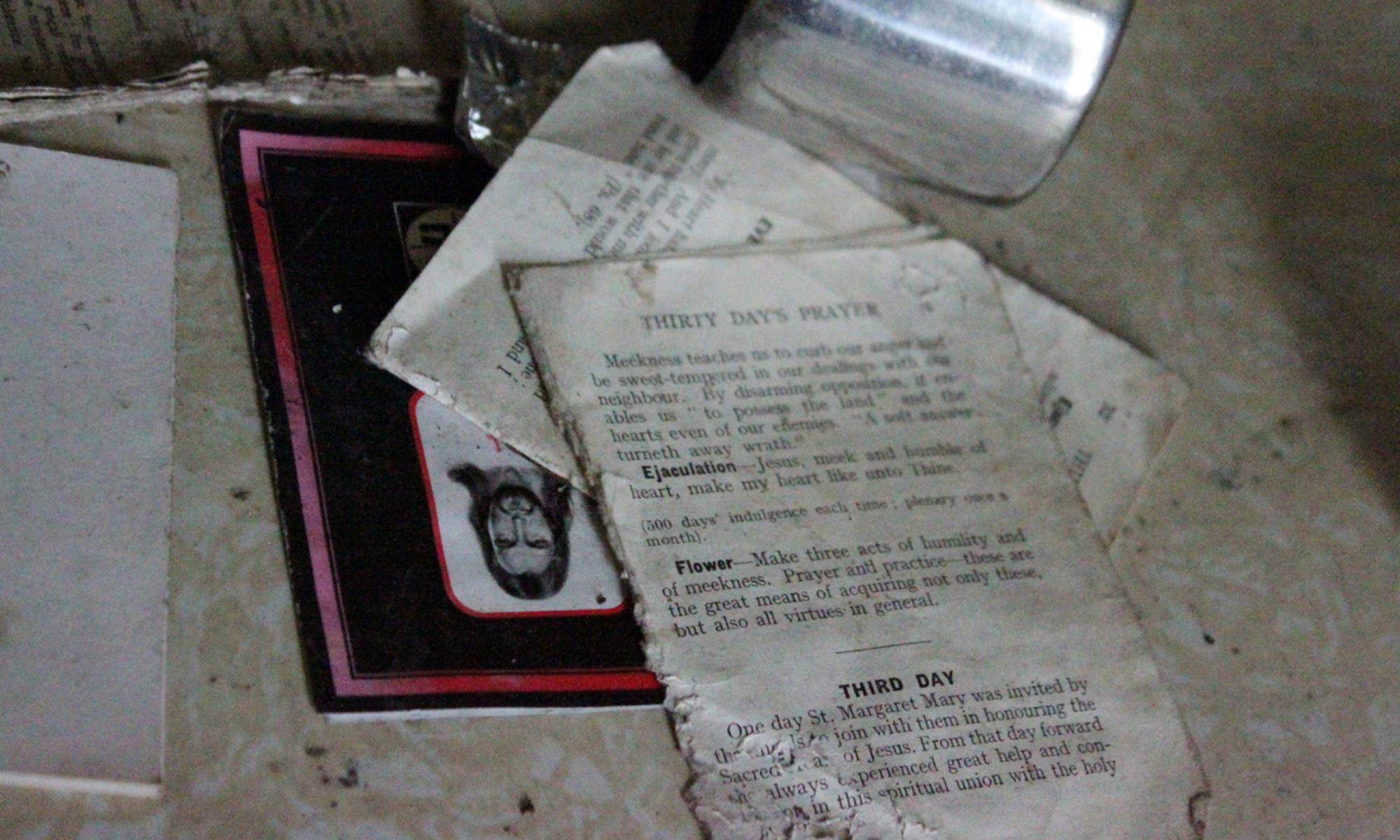

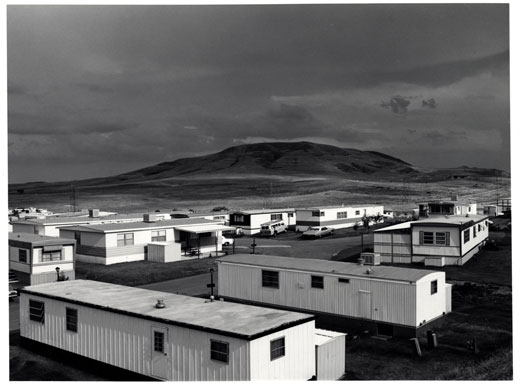

“Ruine des ruines”

Dawn ades, “La photographie et le texte surréaliste” in Explosante fixe

“ces visions litteraires ou photographiques de produits de la civilisation engloutis par une nature triomphante et vorace traduisent symboliquement l’opposition des surréalistes à leur propre culture. Et celà, chose curieuse, se situe dans le prolongement du culte romantique de la nature, propre à l’esthétique de la fin du 18ème siècle, qui prend le parti de l’état sauvage contre la domestiqué, et celui de la nature contre la civilisation.”

Notes from La subversion des images: Surréalisme, Photographie, Film, Exhibition Catalogue at Centre Pompidou

I saw this show in December 2009.

Les images du dehors, Michel Poivert

“definition de la photographie comme empreinte”

“une odieuse laideur dont le pouvoir de fascination révèle la jouissance inavouable que procure le mauvais gout” George Bataille

Un photogramme, à l’instar d’une photographie documentaire, exemplifie une relation interiorisée au monde

Le fantastique moderne, Quentin Bajac

techniques d’enregistrement indicielles

Louis Aragon

“ne conçoit pas de merveilleux en dehors du réel”

“un fantastique, un merveilleux moderne autrement riche et divers”

“La réalité est l’absence apparente de contradiction. Le merveilleux, c’est la contradiction qui apparait dans le réel. Le fantastique, l’au delà, le rêve, la survie, le paradis, l’enfer, la poésie, autant de mots pour signifier le concret” La révolution surréaliste 3

“sentiment du merveilleux quotidien”

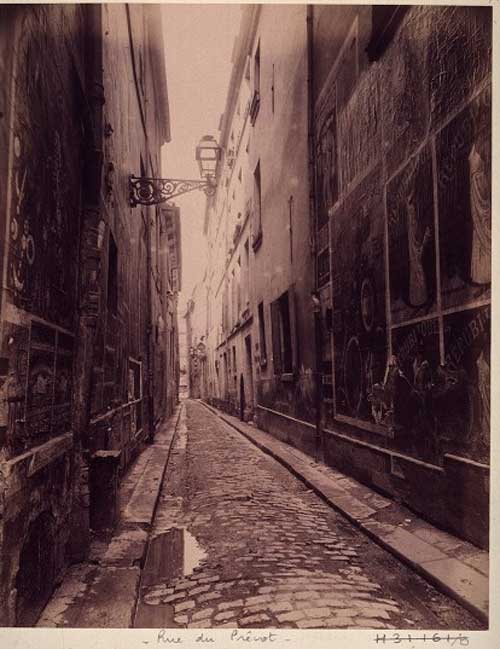

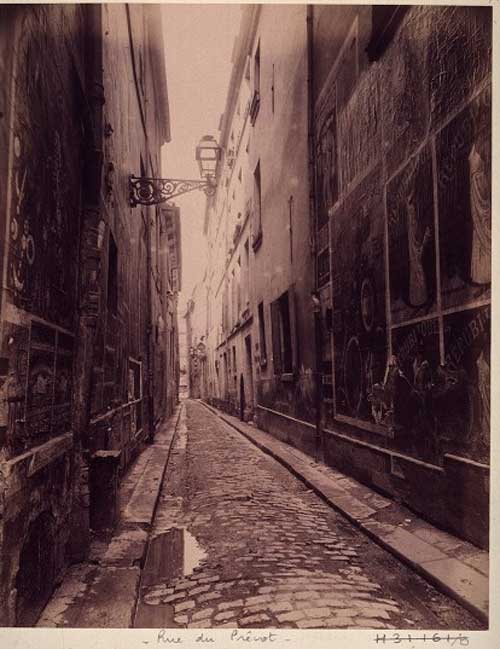

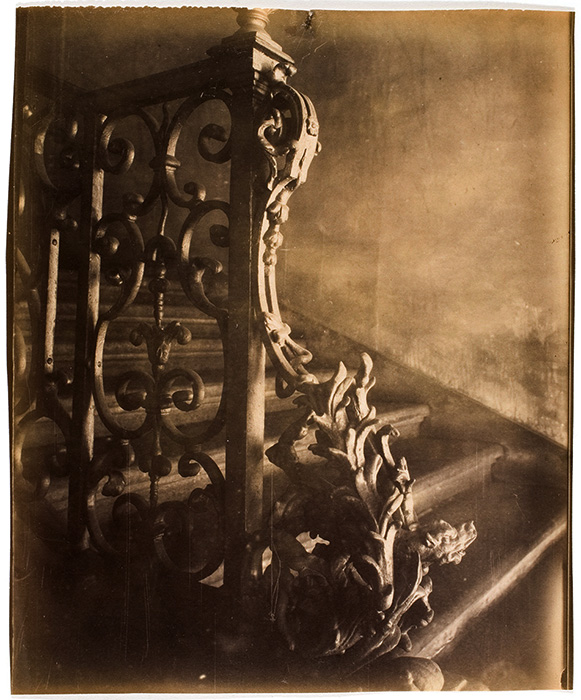

About Eugène Atget, self taught photographer of Paris whom the Surrealist admired:

Waldemar George: « un quart de siècle avant Aragon, il a écrit Le Paysan de Paris en sondant, en dépouillant de sa gangue et en mettant à nu cet immanent mystère qui a pour nom: banalité. »

Albert Valentin: « tout à l’air de se passer au delà, dans la marge, dans le filigrane, dans l’esprit »

« une même poésie spectrale et populaire de la ville. Eloignés des utopies modernistes urbaines contemporaines, ils prennent leur source dans un Paris où seuls les lieux banals et surannés peuvent faire surgir un merveilleux moderne. »

« une nouvelle mythologie moderne urbaine dont les clichés d’Atget, dans leur brutalité primitive, fourniraient une des clefs d’accès. »

« autant de contenus manifestes, d’apparences trompeuses qu’il convient de déchiffrer »

« mettre au jour un contenu latent, souvent chargé de mystère et de percer littéralement l’ombre, lieu de tous les fantasmes »

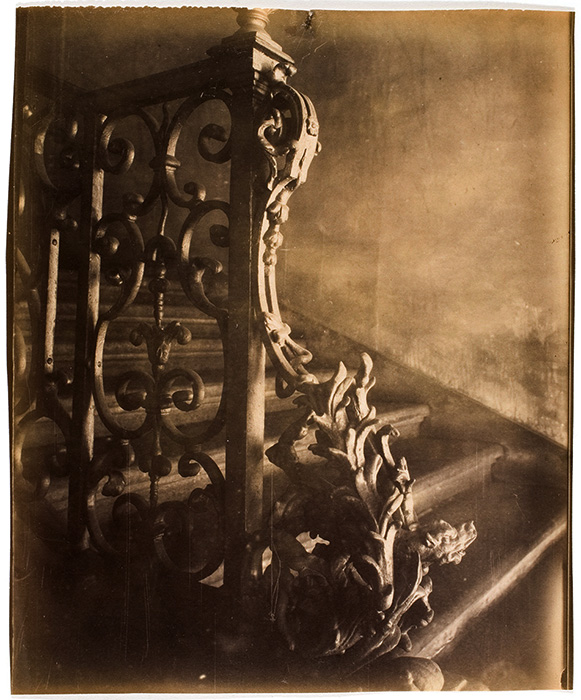

Below some pictures by Atget:

Dali, « Le témoignage photographique »

« la nature intrinsèquement fantastique du médium photographique »

Pierre Mac Orlan, « Masquer sur mesure », 1928

« révélateur d’une puissance merceilleuse »

About the photographs illustrating André Breton’s Nadja:

« hallucinations simples »

André Breton about night in « Les vases Communicants »:

« la grande nuit qui sait ne faire qu’un de l’ordure et la merveille »

This may refer to Brassai’s photographs of Paris by night.

Below some photographs by Brassaï:

Random quotations:

Henri Cartier Bresson p152:

« laisser l’objectif photographique fouiller dans les gravats de l’inconscient et du hasard »

Dali, « Mes toiles au salon d’automne », 1927 p219

voir le monde « d’une manière spirituelle, dans sa plus grande réalité objective »

Freud:

Schaulust = pulsion scopique p220

André Breton, « Le Surréalisme et la peinture » p274

« L’oeil existe à l’état sauvage » = the eye exists in a savage state (he means that people see things instinctively, the sense of sight does not need to be educated, tamed.)

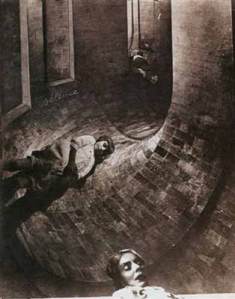

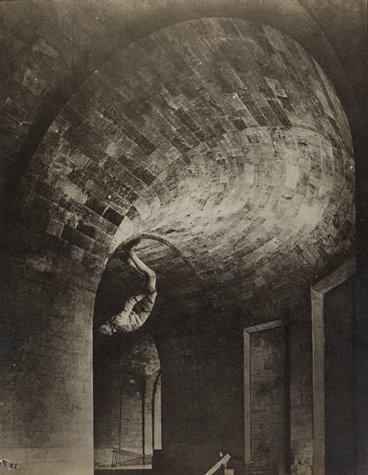

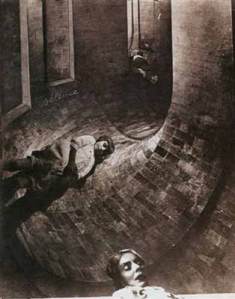

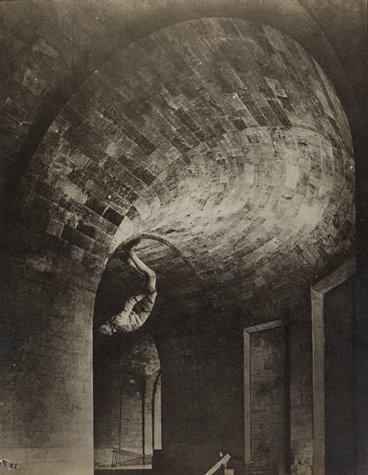

about strange perspectives in Dora Maar’s collages p275:

« les décors sont sombres et composés de perspectives dépravées: une fenêtre disparaît derrière une colonne pour ne jamais reparaître; un couloir penche vers la gauche jusqu’à se tordre; une voûte s’avère à la fois concave et convexe selon le point de vue qu’on adopte. Ainsi les personnages chimériques ont-ils l’air d’errer dans des espaces qui, par leur contiguïté et leur hétérogénéité, ne peuvent qu’être mentaux. »

Warped spaces in Dora Maar collages:

Original Surrealist published material, reprinted

Louis Aragon, « Du décor », 1918, p417

« Doter d’une valeur poétique ce qui n’en possédait pas encore »

Robert Desnos, « Puissance des fantômes », 1928, p418: a poetic ode to cinema and the power of imagination

« Nés pour nous, par la grâce de la lumière et du celluloïd, des fantômes autoritaires s’assoient à notre côté, dans la nuit des salles de cinéma »

« le cinéma ne saurait être que le domaine du fantastique. En vain le réalisme croit-il régner sur les films ».

« Le merveilleux se manifeste où il veut et, quand il veut, il paraît au cinéma à l’insu peut être de ceux qui l’introduisent. »

« Heureux l’homme soumis à ses fantômes. Certes, il connaîtra des nuits désertes, d’inexplicables nostalgies, des mélancolies infinies, le désir sans raison, le spleen, l’implacable spleen. Mais il remettra la terre à sa place parmi les astres et l’homme parmi les créatures. Jamais l’or ne le détournera de son chemin. Jamais un boulet d’esclave n’entravera sa marche. Mieux, tout ce qu’il désirera, il l’obtiendra par la magie même de son imagination et les visites mystérieuses charmeront sa solitude. Libre, il agira librement en toute chose et sorti du dédale terrible de ses rêves, est-il quelque chose sur terre qui pourrait l’épouvanter? […] Initié au fantastique par la seule puissance de la surprise, son esprit connaîtra bientôt la sérénité, née du conflit de son orgueil et de son inquiétude. »

I translate this particular bit because it is very poetic and I like it:

« Fortunate is the man who submits to his ghosts. Sure, he will be prey to deserted nights, unexplainable nostalgies, infinite melancholies, mindless desire and spleen, the merciless spleen. But he will put the Earth back in its place among the stars, and man among the creatures. Never will gold sway him from his path. Never will he be hindered by a slave’s ball and chain. Better, all that he may desire, he will get it by the mere magic of his imagination, and mysterious visits will charm his solitude. Free, he will act freely in all things and, out of the terrible labyrinth of his dreams, is there anything on Earth that could terrify him? […] Initiated into the Fantastic by the mere power of surprise, his mind will soon know serenity, born out of the conflict of his pride and anxiety. »

Note: « ghost » = « fantôme » in French = « fantasma » in Italian (learnt from watching too many Dario Argento subtitled movies 🙂 and also spanish

« Fantasme » in French = « a fantasy » in English

« Fortunate is the man who submits to his ghosts. » I’m wondering whether there is some kind of pun here about fantôme (ghost) -> fantasma → fantasme → « Fortunate is the man who submits to his fantasies. » May be worth looking into the latin root of « fantasme » and « fantôme »

Antonin Artaud, « Sorcellerie et cinéma », 1927, p419

« cette espèce de griserie physique que communique directement au cerveau la rotation des images »

« cette sorte de puissance virtuelle des images va chercher dans le fond de l’esprit des possibilités à ce jour inutilisées. Le cinéma est essentiellement révélateur de toute une vie occulte avec laquelle il nous met directement en relation. Mais cette vie occulte, il faut savoir la deviner. »

« le cinéma […] dégage un peu de cette atmosphère de transe éminement favorable à certaines révélations. »

« un certain domaine profond tend à affleurer à la surface »

« Le cinéma me semble surtout fait pour exprimer les choses de la pensée, l’intérieur de la conscience, et pas tellement par le jeu des images que par quelque chose de plus impondérable qui nous les restitue avec leur nature directe, sans interpositions, sans representations. Le cinéma arrive à un tournant de la pensée humaine, à ce moment précis où le langage usé perd son pouvoir de symbole, où l’esprit est las du jeu des representations. La pensée claire ne nous suffit pas. Elle situe un monde usé jusqu’à l’écoeurement. Ce qui est clair est ce qui est immédiatement accessible, mais l’immédiatement accessible est ce qui sert d’écorce à la vie. Cette vie trop connue et qui a perdu tous ses symboles, on commence à s’apercevoir qu’elle n’est pas toute la vie. »

I translate this bit because it is crucial:

« To me, cinema seems to be made to express thoughts, the inside of the consciousness, and not so much through the play of images than through something more fleeting that communicates them to us with their direct nature, without interpositions, without representations. Cinema was discovered at a turning point of human thought, at this very moment when overused language has lost all of its symbolic power, when the mind is weary of the game of representations. Clear thought is not enough. It paints a word overused to nausea. What is clear is what is immediately accessible, but what is immediately accessible is nothing but the mere surface of life. This life that we know too well, that has lost all its symbols, we start to realise that it is not the whole of life. »

Benjamin Fondane « Du muet au parlant: grandeur et décadence du cinéma » 1930

« un nouveau moyen d’expression qui non seulement remplacerait la parole mais la mettrait en échec, soulignerait son creux; exiger d’autre part du spectateur une sorte de collaboration, ce minimum de sommeil, d’engourdissement nécessaire, pour que fût balayé le décor du signe et que prît forme à sa place le réel du rêve.

Que le spectateur perdit pied, c’est tout ce que le cinéma voulait. »

Albert Valentin « Eugène Atget, 1856-1927 » 1928

« tout a l’air de se passer au-delà »

« Le reste est au-delà, vous dis-je, dans la marge, dans le filigrane, dans l’esprit, à la portée du moins perspicace ».

Brassaï « Images latentes » 1932

juste cette expression « images latentes »

Dali « le témoignage photographique » 1929

« essentiellement le véhicule le plus sûr de la poésie »

« percevoir les plus délicates osmoses qui s’établissent entre la réalité et la surréalité »

« l’enregistrement d’une réalité inédite »

Raoul Ubac « L’envers de la face » 1942

« Une image, et surtout une image photographique, ne donne du réel qu’un instant de son apparence. Derrière cette mince pellicule qui moule un aspect des choses, à l’intérieur de cette image il en existe à l’état latent une autre, ou plusieurs autres superposées dans le temps et que des opérations le plus souvent dues au hasard décèlent brusquement. »

Jean Goudal « Surréalisme et cinéma » 1925

« Au cinéma comme dans le rêve, le fait règne en maître absolu. L’abstraction perd ses droits. Aucune explication ne vient légitimer les gestes des héros. Les actes succèdent aux actes, portent en eux mêmes leur justification. Et ils se succèdent avec une telle rapidité que nous avons à peine le temps d’évoquer le commentaire logique qui pourrait les expliquer, ou tout au moins les relier. »

« hallucination consciente »

« cette fusion du rêve et de l’état conscient »

« ces images mouvantes nous hallucinent, mais en nous laissant une conscience confuse de notre personnalité et en nous permettant d’évoquer, si c’est nécessaire, les disponibilités de notre mémoire. »

« Dans le langage, la donnée première est toujours la trame logique. L’image naît à propos de cette trame et s’y ajoute pour l’orner, pour l’éclairer. Au cinéma, la donnée première est l’image, qui, à l’occasion, et point nécessairement, entraîne à sa suite des lambeaux rationnels. »