This post won’t be a well thought-out well organised dissertation on some subject but rather a list of issues/uncertainties I have about how to pitch my research project according to the structure given to us last week. In particular, how to phrase the research question and how to pitch it within the contextual categories: history, contemporary, critical theory, parallel theory, projective or generative theory.

The main problem I have is I know what types of artwork I want to make but am unsure about how to pitch it within a coherent research project. It’s like there are a couple of different threads I want to explore, and they are all somehow related to the big soup of things I may call “interests, obsessions and inspiration” which share lots of similar themes but I’m not fully sure how I may knot these threads into a bullet-proof research question.

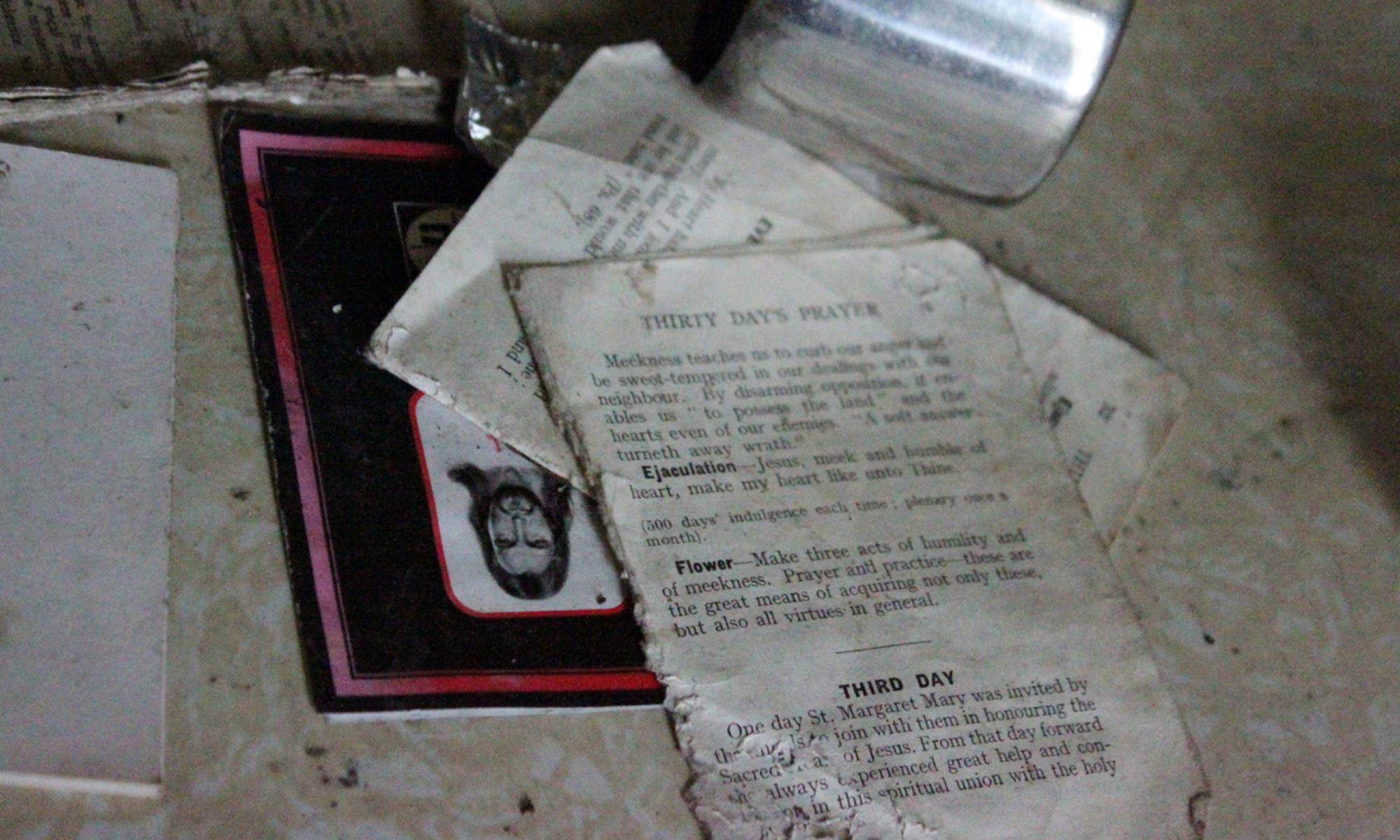

Bluntly, this is how I came up with my initial research proposal: I have been doing the ghost houses for 3 years because I like exploring them, I find them fascinating. I had been doing (and went on doing) other things I personally found equally interesting before doing the ghost houses (photographs of woods where light was very fairy tale-like, random wood sculptures, dream paintings, found objects assemblage) but those were constantly rejected from exhibitions. Then out of nowhere, the ghost houses started being accepted to about a third of the exhibitions I offered them to, with on top of that quite a few of “sincere” (i.e. personalised rejection letter with comments, not standard letter) sorry-we-think-they’re-great-but-don’t-quite-fit-the-subject refusals. To me it was an amazing success rate. It seemed when I started the ghost houses, I had unknowingly started making fashionable artworks !!! Indeed, when you look in AN, there are quite a lot of events going on about space, urban, the built environment and such. These is obviously a fashion going on about that. I was completely unaware of it when I started the ghost houses, I did them because I found them fascinating. But, hey, I’m not suicidal either, if one of the things I do is fashionable by sheer luck, it has to be in my research project !

So exploring derelict places became part of the research project. It could not, however, be the complete research project for several reasons:

1) I don’t live near the ghost houses and can only explore them in summer (derelict places in England are heavily guarded old public institutions that require a lot of jackass skills to get in). Even if I lived near them, I’m not sure I would like to spend all my week ends in places where there might me asbestos, pigeon droppings and such. A couple of times per year wearing a good dust mask won’t kill me, but I would not like to spend my life in there.

2) You cannot predict the productivity of a ghost house. It may be locked up, wrecked, empty, too dark or without anything interesting in it. It is not only in the Art world that space/the built environment has become fashionable over the last 2 years, urban exploration as a hobby has become hype, with dedicated websites flourishing. Some urban explorers seek fame and glory from it, advertising their explorations with exact location name as trophies. The consequence being that the place owner just has to google the name of their property to learn about the unwanted visitor, and heavily lock up the place, making it inaccessible to others (I have even been wondering whether this consequence was not intentional. After all, the rarer the trophy, the more valuable). The best places I had planned to visit this summer were heavily locked up after some high visibility reports were put online about them … Thankfully, this type of behaviour is not too common and most urban explorers are relatively discreet and helpfully share tips about access to places. While I’m at it, I just would like to state than the urban exploration moto is “take nothing but photographs, leave nothing but footprints”, so it is a peaceful, non destructive activity.

3) I might get bored of the ghost houses, in which case I’ll stop, however fashionable they might be.

So the research project had to have other things in it. I had been making paintings of dreams, and love cinema exploring consciousness, so the obvious was to make videos inspired by dreams and inner worlds.

Then came the issue of how to knot those 2 apparently unrelated threads. This is the main issue I am researching in books at the moment. Instinctively, I know space and consciousness are related, but I do not have a couple of smart quotations to prove it (tough luck). Why do I know it instinctively ? One of my favourite paintings is Birthday by Dorothea Tanning. The corridor seems to go on indefinitely, there is a mirror on the left but the real space does not seem any more real than the reflection. It seems this beautiful strange house is not the outer world but the (infinite) inner world of the artist.

I’ve always seen my house as a shelter: I can make it look the way I like (since a teenager, I have skimmed bric a brac shops and garage sales, lovingly doing up old fashioned objects in the colors and patterns I like), and in it I can do whatever (harmless thing) I like without the fear of being marked as odd. To me a house is a private place where people are free to be themselves away from the judgemental looks of others. See also Virginia Woolf’s essay “A room of one’s own”: people need a private space to be able to think independently. When I am invited in other people’s houses, I look at the colours they chose, the objects they like and I feel I know the host more intimately thanks to those. I see their house as the closest approximation to a physical projection of somebody’s inner world. Many Raw artists actually takes this statement literally, and turn their whole house into a huge artwork, creating their own self contained universe with a unique mythology.

A recurrent theme in films and books set in the former Soviet Union (Dr Zhivago, The Master and Margarita) are the dreadful communal housing, and the nosiness, gossips, mutual spying that came with them. What was probably started as an emergency war-time measure to give decent housing to everyone was soon turned into a control instrument to make people conform by encouraging neighbours to spy on and denounce each other. The recurrence of the theme shows how traumatising it must have been for people to be suddenly deprived of their private space like this. One of the selling point of Capitalism was that, within Capitalism, contrary to the Eastern Bloc, people were granted the right to individuality and privacy. Yet, today, many young adults with decent, steady jobs cannot afford a private space and are forced to live with perfect strangers met through the small ads well into their late 30s. Flatshare are contemporary Communal housing. It is not greed but flatshare-phobia that made me take a boring but reasonably lucrative engineer job in the first place. Open space offices are another contemporary example of the use of space as an instrument of mind control. In contemporary UK, people do not talk of “houses” anymore but of “property”. What used to be an intimate space where people were free to be themselves is now a commodity passed from hand to hand every 3 years in order to reap the profit from speculation on it.

In many movies, madness manifests itself as a distortion of space and time. In David Lynch’s films, there a recurring image of a corridor with drapes whenever a character goes insane, looses grip on reality or feels a menace. In many of his films, the inside architecture of the houses where the character live do not make sense (at least not within Euclidian geometry …): the inside seems far too big compared to the outside, there seem to be doors and corridors leading from everywhere to everywhere, characters walk around the house and they seem to go through the whole of it as though the house was built as an endless circle. In many interviews, Lynch confesses an obsession with houses: he sees them as self contained worlds were dreadful things happen, unknowingly of the outside world. So his vision of houses is tainted with menace and claustrophobia. Strange architecture is also present in German expressionist movies. In Last Year in Marienbad, the characters seem trapped in the immense hotel, going round in endless spatio-temporal circles, unable to leave the space until their mind makes sense of what is happening. In Polanski’s Repulsion, Catherine Deneuve, alone with her hallucinations, traps herself in her flat, a refuge turned menacing prison. Generally, in movies, people often drive themselves mad in close spaces (Kubrick’s Shining). In popular culture, the haunted houses and poltergeist phenomenon suggest a strong link between people’s minds and the places they used to inhabit.

So a house, a shelter, place and freedom and projection of one’s inner world may very quickly turns into a prison, a projection of one’s anxieties and obsessions. Where/when is the turning point or the trigger, or are both aspects constantly present ? Are they the same thing ? This question is definitely one of my obsessions.

Yet, I don’t think I want to call my research project “space and consciousness” or something like that, because this is not all I see in the ghost houses. Another important aspect of them is the unpremeditated compositions and putting my own meaning on something that already exists by itself. I feel it is an important part of my art process as I was already exploring something similar when I made the random wood sculpture. So I don’t want to leave this aspect out of the research project.

When I said “madness manifests itself as a distortion of space and time”, there is also the time factor that I could not explore in photography and paintings, but that I will use in moving image.

So in the end, the only common thing I could find in my obsessions and interests is subjectivity. The subjectivity of one individual’s vision. The problem is, this does not make a research question ! So I decided that the best solution was to call the project Digital Surrealism, since the surrealists were themselves interested in many of the things I am want to explore (dreams, consciousness, randomness). That will do the trick, I thought happily …

But then I’m reading “Surrealism and Cinema” by Michael Richardson, where he says that David Lynch’s work has nothing to do with Surrealism because Lynch has no desire to change the world, and his interviews show he has a bad understanding of what Surrealism was. Indeed Lynch is no revolutionary (though I have no clue what his political leanings are, and I don’t care). The interviews in question, I don’t remember them if I read them so I cannot comment on the level of expertise in Lynch’s understanding of Surrealism within Art History until I read them again. However, my humble opinion is that, even if David Lynch was a trotskyist and held a Phd in Art History about Surrealism, he could not be a Surrealist anyway because Surrealism as an Art movement died in the 60s at latest. In passing, Richardson does not comment about Lynch’s use of images he does not know the meaning of (the blue box in Mulholland Drive) and his use of altered states of consciousness (namely transcendental meditation) in order to find ideas for artworks without being censored by his “Conscious”: he dismisses Lynch as a neo/post-surrealist purely on the ground of intent, ignoring method or process.

Anyway, even when Surrealism was alive, there was no clear definition of who was or was not a Surrealist. Breton and the hardcore wrote theoretical texts about the principles of Surrealism. Some of these texts are better forgotten for Surrealism’s sake, especially homophobic rants and ludicrous dogma about women’s say in the practical organisation of sexual intercourse. But many artists gravitated around Surrealism without being formally part of the movement, which did not prevent them from being invited to take part in surrealist exhibitions. They were attracted mostly by its aura of freedom. This included many women artists without formal training, who were not bothered by Breton’s outdated views on female sexuality, or simply granted them the amount of attention they deserved … Some of these artists did not want to join to preserve their independence, because the authoritarian personality of Breton annoyed them (Leonor Fini), or simply because they could not be bothered (especially Belgian painters who were away from Paris). Later on, Breton became more dogmatic and starting “excluding” lots of artists for all kinds of dubious reasons. This did not prevent those excluded dissidents from going on making their work, with or without Breton’s approval.

Even if the theoretical writings about Surrealism were completely free of rubbish, no contemporary artists could be expected to follow them literally nowadays. They were written in the 20s and 30s and the social conditions in which the artwork are produced have drastically changed.

All this to say that what at first seemed a convenient title now seems like a needlessly dangerous magnet for criticism by hair splitters who think they have the authority to decide who is or is not influenced by Surrealism in 2009. There was a hint in the chat that in the “contemporary context” part of our project proposal, we could give names of current academic research. So this seems to imply that the way we pitch our research proposal could influence academic opportunities we have at the end of the MA. With that in view, it seems suicidal to choose a title that is like a criticism magnet, however convenient it might have sounded at first.

So it’s now 00.01, I have written 2352 words and I still don’t know how to call my research project …