“Fantasy, the Uncanny and Surrealist Theories of Architecture”, Anthony Vidler (2003)

“Rather what Surrealism motivated was the uncanny of the Other, which for Surrealism was the ‘real’ – the uncanny sense that the normal was nothing more than a complex of repressed objects. In the aesthetic sense of Surrealism, this normal was modernism itself and the uncanny of Surrealism was no more than the repressed of modernism, an apparent normal that in fact was a mask for the ‘real’ pathological.

In architectural terms, this search for modernism’s repressed underlife was concentrated in three domains – domains that the modernists had clearly and polemically identified as the basis of their attack on tradition: the solid, load-bearing wall that afforded traditional protection and privacy; the bourgeois house and its kitsch-like trappings of ‘home’ or ‘Heimat’; and the objects of everyday life, which, while for the most part mass-produced, were still encumbered with ornament and encrusted with historical references. Against these three hold-outs of tradition in modernity “

“All posed a volatile and elusive sensibility of mental-physical life against what was seen as a sterile and over-rationalized technological realism: the life of the interior psyche against the externalising ratio.”

Freud in the Uncanny: ‘over-accentuation of psychical reality in comparison with material reality,’

Sigfried Giedion observes of the interiors of Ernst’s Une Semaine de bonté:

“The room, as nearly always, is oppressive with assassination and non-escape”

“Surreal Dreamscapes: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades”, Michael Calderbank (2003)

On Benjamin’s essay of 1925 entitled ‘Dream-Kitsch’:

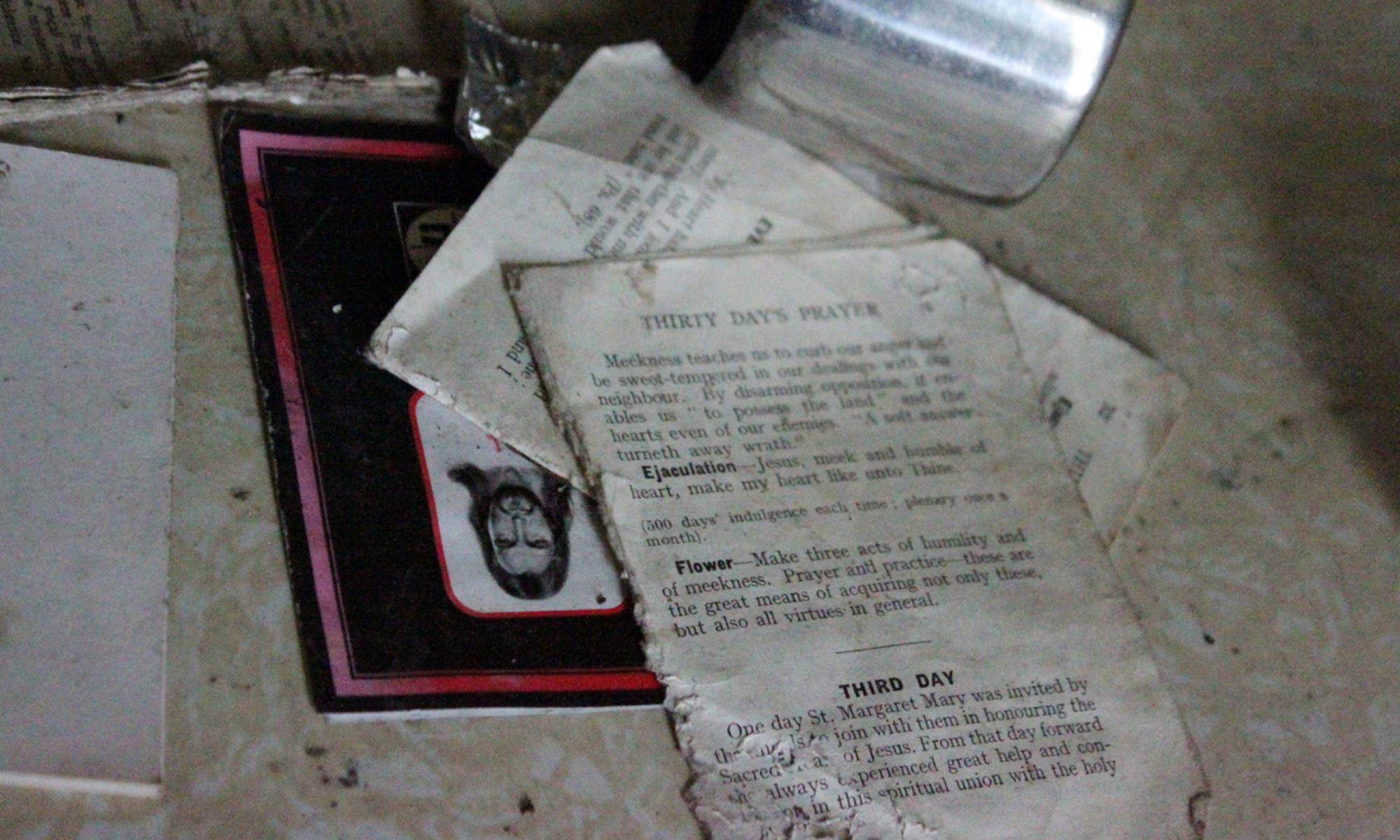

“this inter-penetration of the two realms is not a ‘natural’ constant, but a historically specific phenomenon. 10 Kitsch objects, the banal by-products of culture subsumed under the logic of industrial production, are assimilated into dreams, thereby obscuring the oneiric ‘blue horizon’ of the Romantics, with a ‘grey coating of dust’. Correspondingly, as Marx first diagnosed with his analysis of the commodity fetish, at the height of capitalist modernity, ‘ordinary’ commodities become invested with a magical, quasi-religious and dreamlike aura.”

“In ‘Konvolut L’, Benjamin notes: ‘Arcades are houses or passages having no outside – like the dream.’”

Comparing Benjamin and Breton:

“For both writers, what is significant is not the waking state per se, which could quite easily carry on in the same drearily prosaic way, but the moment when consciousness is shocked into the recognition of possible forms of cognitive experience from which it is excluded in reality. Both writers also, therefore, develop a notion of a single material reality, in which ‘dream’ and ‘waking’ experience are both inextricably grounded, and which progresses not in a gradual, seamless, linear continuum, but instead proceeds unevenly in jolts, leaps and unexpected reversals.”

“Giorgio de Chirico and surrealist mythology , Roger Cardinal (2004)

What is most modern in our time frequently turns out to be the most archaic.

GuyDavenport

“a collection of talismanic embodiments of the twinned novelty and absurdity of modern life. By deliberately fetishising the bric-à-brac of twentieth-century urban culture, surrealism was able to draw up a formula for the surrealist Marvellous and to elicit a striking mythology out of the banalities of the contemporary world. “

On Aragon’s Le Paysan de Paris:

“a kind of archaeology of the contemporary unconscious “

‘the vertigo of the modern’ [‘le vertige du moderne’]. (Aragon’s words)

Breton’s essay on de Chirico (1920):

‘re-appraise the basic perceptions of time and space’ [‘reviser les données sensibles du temps et de l’espace’].

Aragon’s quotation, unknown book:

‘Though substituted for the natural myths of antiquity, [the new myths] cannot be truly opposed to them, for they derive all their strength, all their magic, from the selfsame source.’

‘Substitués aux antiques mythes naturels, [les mythes nouveaux] ne peuvent leur être réellement opposés, car ils puisent leur force, leur magie à la même source.’

“The Uncanny”, Margaret Iversen, 2005

“Schelling defined it [The uncanny] as something that should have remained hidden but has come to light. In a more Freudian idiom, it is a feeling prompted by the return of the repressed.”

“The scene for the emergence of uncanny strangeness is, after all, the familiar, conventional or banal. This is so because the ‘familiar’ is constituted by the repression of childhood traumatic experience or the real of unconscious fantasy. The familiar must inevitably have a simulacral quality because the real has been expelled. David Lynch beautifully demonstrates this mutual dependence in his film, Blue Velvet (1986). The white picket-fenced world of Lumberton shown in the opening sequence has such stereotypical clarity that one’s gaze slides right off the image, unable to get any purchase. Lynch makes it clear that the bourgeois residential area has this two-dimensional simulacral quality precisely because reality (here a criminal underclass and the unconscious) has been marginalized, banished to the other side of the tracks. For me, the uncanny is not the simulacrum itself, but that which agitates its shiny surface.”

Dana MacFarlane, 2003, reviews “City Gorged With Dreams: Surrealism and Documentary Photography in Interwar Paris” by Ian Walker

“One of the explicit claims Walker makes is that the ‘stricter’ the reality presented by the photograph, the more potentially subversive and surreal its effect. In the process of being represented photographically, the everyday world is transformed. The surreal appears in those photographs in which the logic of realism presented by the photograph is interrogated, undermined and transformed.”

Breton’s Nadja: ‘the space between’

‘Surrealism lies at the heart of the photographic enterprise: in the very creation of a duplicate world, of a reality in the second degree, narrower but more dramatic than the one perceived by natural vision.’ Susan Sontag, ‘Melancholy Objects’ in On Photography (New York: Penguin, 1979), p. 52.