Surrealism The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia (1929)

“Life only seemed worth living where the threshold between waking and sleeping was worn away in everyone as by the steps of multitudinous images flooding back and forth, language only seemed itself where, sound and image, image and sound interpenetrated with automatic precision and such felicity that no chink was left for the penny-in-the-slot called “meaning”.”

“In the world’s structure dream loosens individuality like a bad tooth. This I loosening of the self by intoxication is, at the same time, precisely the fruitful, living experience that allowed these people to step outside the domain of intoxication.”

“ But the true creative overcoming of religious illumination certainly does not lie in narcotics. It resides in a profane illumination, a materialistic, anthropological inspiration.”

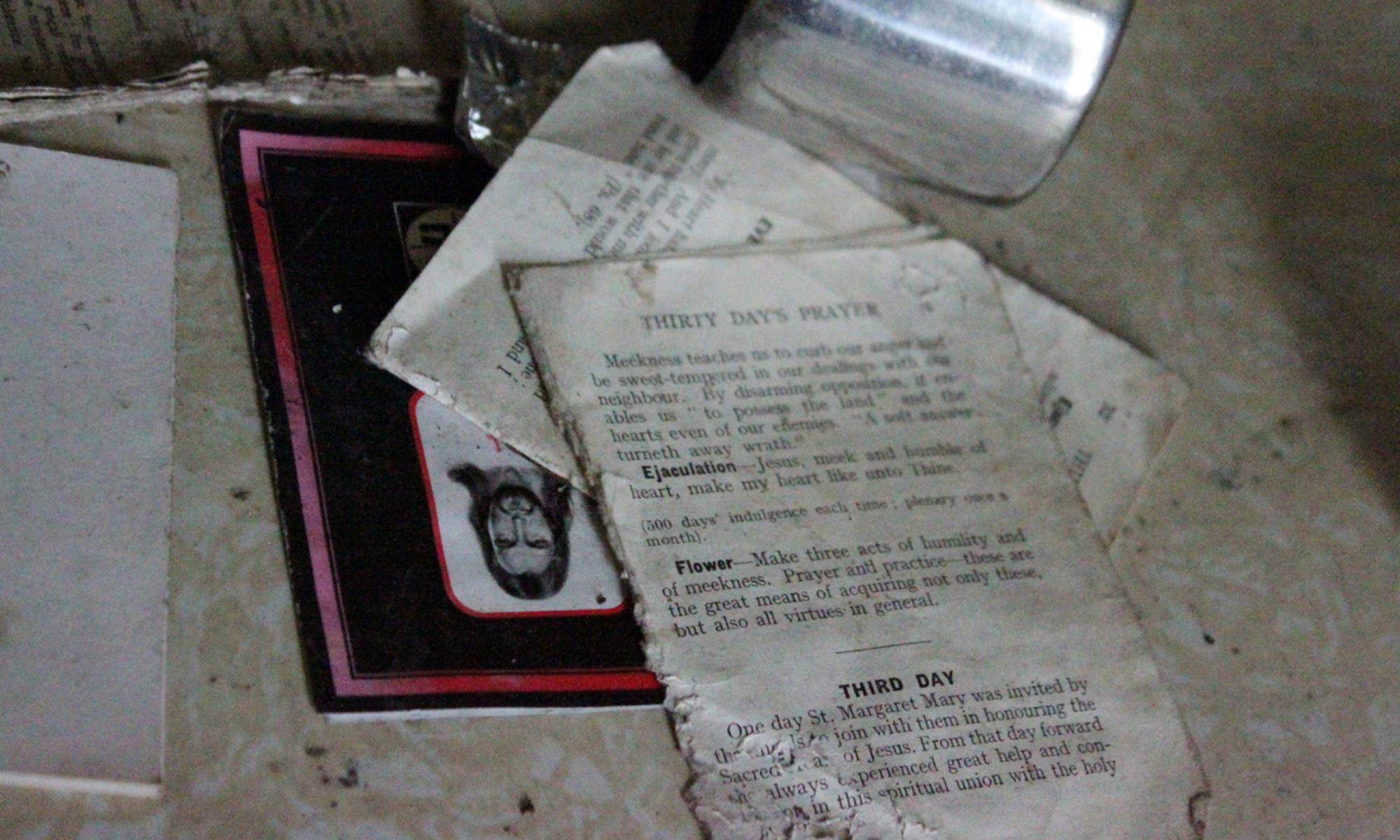

“ perceive the revolutionary energies that appear in the “outmoded”, in the first iron constructions, the first factory buildings, the earliest photos, the objects .that have begun to be extinct, grand pianos, the dresses of five years ago, fashionable restaurants when the vogue has begun to ebb from them. […] No one before these visionaries and augurs perceived how destitution—not only social but architectonic, the poverty of interiors/enslaved and enslaving objects- can be suddenly transformed into revolutionary nihilism.”

“convert everything that we have experienced on mournful railway journeys (railways are beginning to age), on Godforsaken Sunday afternoons in the proletarian quarters of the great cities, in the first glance through the rain-blurred window of a new apartment, into revolutionary experience, if not action. They bring the immense forces of “atmosphere” concealed in these things to the point of explosion.”

“And no face is surrealistic in the same degree as the true face of a city. No picture by de Chirico or Max Ernst can match the sharp elevations of the city’s inner strong-holds, which one must overrun and occupy in order to master their fate and, in their fate, in the fate of their masses, one’s own.”

“The Surrealists’ Paris, too, is a “little universe”. That is to say, in the larger one, the cosmos, things look no different. There, too, are crossroads where ghostly signals flash from the traffic, and inconceivable analogies and connections between events are the order of the day. It is the region from which the lyric poetry of Surrealism reports.”

“ the deeply grounded composition of an individual who, from inner compulsion, portrays less a historical evolution than a constantly renewed, primal upsurge of esoteric poetry”

“ the philosophical realism of the Middle Ages was the basis of poetic experience. This realism, however—that is, the belief in a real, separate existence of concepts whether outside or inside things—has always very quickly crossed over from the logical realm of ideas to the magical realm of words. And it is as magical experiments with words, not as artistic dabbling, that we must understand the passionate phonetic and graphical transformational games that have run through the whole literature of the avant-garde”

Apollinaire, L’esprit nouveau et les poetes:

“ their synthetic works create new realities the plastic manifestations of which are just as complex as those referred to by the words standing for collectives”

about Dostoyevsky:

“No one else understood, as he did, how naive is the view of the Philistines that goodness, for all the manly virtue of those who practise it, is God-inspired; whereas evil stems entirely from our spontaneity, and in it we are independent and self-sufficient beings.”

I think the Surrealists moved away from this preoccupation and it’s rather George Bataille that continued to pursue this idea ?

“ we penetrate the mystery only to the degree that we recognize it in the everyday world, by virtue of a dialectical optic that perceives the everyday as impenetrable, the impenetrable as everyday […] The reader, the thinker, the loiterer, the flaneur, are types of illuminati just as much as the opium eater, the dreamer, the ecstatic. And more profane. Not to mention that most terrible drug—ourselves—which we take in solitude.”

The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935)

“Works of art are received and valued on different planes. Two polar types stand out; with one, the accent is on the cult value; with the other, on the exhibition value of the work. Artistic production begins with ceremonial objects destined to serve in a cult. One may assume that what mattered was their existence, not their being on view. […] With the different methods of technical reproduction of a work of art, its fitness for exhibition increased to such an extent that the quantitative shift between its two poles turned into a qualitative transformation of its nature. This is comparable to the situation of the work of art in prehistoric times when, by the absolute emphasis on its cult value, it was, first and foremost, an instrument of magic. Only later did it come to be recognized as a work of art. In the same way today, by the absolute emphasis on its exhibition value the work of art becomes a creation with entirely new functions, among which the one we are conscious of, the artistic function, later may be recognized as incidental. This much is certain: today photography and the film are the most serviceable exemplifications of this new function.”

“The cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead, offers a last refuse for the cult value of the picture. For the last time the aura emanates from the early photographs in the fleeting expression of a human face. This is what constitutes their melancholy, incomparable beauty. But as man withdraws from the photographic image, the exhibition value for the first time shows its superiority to the ritual value. To have pinpointed this new stage constitutes the incomparable significance of Atget, who, around 1900, took photographs of deserted Paris streets. It has quite justly been said of him that he photographed them like scenes of crime. The scene of a crime,

too, is deserted; it is photographed for the purpose of establishing evidence. With Atget, photographs become standard evidence for historical occurrences, and acquire a hidden political significance. They demand a specific kind of approach; free-floating contemplation is not appropriate to them. They stir the viewer; he feels challenged by them in a new way. At the same time picture magazines begin to put up signposts for him, right ones or wrong ones, no matter. For the first time, captions have become obligatory. And it is clear that they have an altogether different character than the title of a painting. The directives which the captions give to those looking at pictures in illustrated magazines soon become even more explicit and more imperative in the film where the meaning of each single picture appears to be prescribed by the sequence of all preceding ones.”

Severin-Mars:

“What art has been granted a dream more poetical and more real at the same time! Approached in this fashion the film might represent an incomparable means of expression.”

Werfel:

“The film has not yet realized its true meaning, its real possibilities. . . these consist in

its unique faculty to express by natural means and with incomparable persuasiveness all that is fairylike, marvelous, supernatural.”

“art has left the realm of the “beautiful semblance” which, so far, had been taken to be the only sphere where art could thrive”

“the representation of reality by the film is incomparably more significant than that of the painter, since it offers, precisely because of the thoroughgoing permeation of reality with mechanical equipment, an aspect of reality which is free of all equipment. And that is what one is entitled to ask from a work of art.”

“The greater the decrease in the social significance of an art form, the sharper the distinction between criticism and enjoyment by the public. The conventional is uncritically enjoyed, and the truly new is criticized with aversion”

“The camera introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses.”

“this is at bottom the same ancient lament that the masses seek distraction

whereas art demands concentration from the spectator. […] Distraction and concentration form polar opposites which may be stated as follows: A man who

concentrates before a work of art is absorbed by it. He enters into this work of an the way legend tells of the Chinese painter when he viewed his finished painting. In contrast, the distracted mass absorbs the work of art.”

A small History of Photography

“The most precise technology can give its product a magical value, such as a painted picture can never have for us. No matter how artful the photographer, no matter how carefully posed his subject, the beholder feels an irresistible urge to search such a picture for the tiny spark of contingency, of the Here and Now, with which reality has so to speak seared the subject, to find the inconspicuous spot where in the immediacy of that long forgotten moment the future subsists so eloquently that we, looking back, may rediscover it. For it is another nature that speaks to the camera than to the eye: other in the sense that a space informed by human consciousness gives way to a space informed by the unconscious.”

“optical unconscious”

“photography reveals in this material the physionimic aspects of visual worlds which dwell in the smallest things, meaningful yet covert enough to find a hiding place in waking dreams, but which, enlarged and capable of formulation, make the difference between technology and magic.”

“Atget was an actor who, disgusted with the profession, wiped off the mask and set about removing the make-up from reality too. […] He looked for what was unremarked, forgotten, cast adrift, and thus such pictures too work against the exotic, romantically sonorous names of the cities; they pump the aura out of reality like water from a sinking ship. What is aura, actually? A strange weave of space and time: the unique appearance or semblance of distance, no matter how close the object may be. […] The stripping bare of the object, the destruction of the aura, is the mark of a perception whose sense of the sameness of things has grown to the point where even the singular, the unique, is divested of its uniqueness – by means of its reproduction.”

“ a salutory estrangement between man and his surroundings”

“The camera is […] ever readier to capture fleeting and secret moments whose images paralyse the associative mechanisms in the beholder.”